energy.wikisort.org - Power_plant

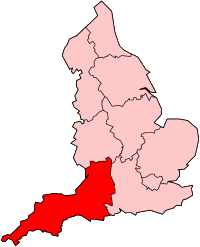

United Downs Deep Geothermal Power is the first geothermal electricity project in the UK. It is the natural progression of the Camborne School of Mines led Cornish Hot Dry Rocks (HDR) project, undertaken in the 1980s at Rosemanowes Quarry, designed to test and prove the theory of inducing a fracture network within the heat-producing granite to create a geothermal reservoir. Situated near Redruth in Cornwall (UK), the project has now proven that harnessing geothermal energy is possible in the UK, encountering temperatures and fluid flow rates that are capable of driving a steam turbine to generate electricity.[1][2]

Initiated in 2009,[3] the development is owned and operated by Geothermal Engineering Ltd. (GEL), a privately owned British company founded in 2008 specialising in the development of geothermal resources. The drilling site selected is on the United Downs industrial estate, chosen both for its geological setting and its surface attributes with existing grid connection, close proximity to access roads and limited anticipated impact on the local communities.[2] Drilling began in 2019, with testing completed by mid-2021. By mid-2023 it is estimated that the power plant will generate between 1 and 3 MW of electricity, which will be sold to the National Grid via the UK's first Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) for deep geothermal electricity with Ecotricity.[4][5] Excess thermal energy will also be distributed locally, with district heating planned to local housing developments and heat-intensive businesses.

The geothermal system being employed to generate power at United Downs targeted a radiogenic granite batholith that exhibits enhanced permeability due to its intersection with the Porthtowan Fault Zone. This zone of enhanced permeability was intersected by both the production well (5,275 m measured depth) and the injection well (2,393 m measured depth). During planned operations, hot fluids occurring naturally at more than 5km depth within the granite will be pumped upwards through the deep production well to be used as an electrical and thermal energy source.[6][7][8][9] Resulting cooled fluids are then reinjected into the shallower injection well for gradual recycling into the deep reservoir through natural fractures in the granite, re-capturing its radiogenic heat. The water used for injecting into the reservoir is natural, deep groundwater that does not affect the local water supply.

History

It took 5 years to secure appropriate funding for the project from a combination of the European Regional Development Fund, Cornwall Council & Private Investors.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

This funding allowed GEL to drill two deep wells from the United Downs site into a target geological structure - the Porthtowan Fault Zone - between November 2018 and June 2019. The geothermal production well reached a depth of 5,275 m and the fluid injection well 2,393 m.[1][2] Contracts for drilling and site equipment were tendered and awarded following European guidelines. Drilling then started on 8 November 2018 with UD-1, the production well, and drilling of the injection well started on 11 May 2019, reaching total depth on 29 June 2019.[1][2]

Between August 2020 and July 2021, both wells underwent a series of injection tests to analyse the hydrology within the fractured geothermal reservoir. In addition, in July 2021, full reservoir testing (simultaneous production and injection) was undertaken for seven days.[2] These tests provided the technical clarity required to commit to commissioning a power plant on site, principally in terms of estimating the range of safe fluid flow rates and monitoring for microseismicity. During this process, the reservoir was destressed to prevent microseismic events occurring during long term operation.[2][17] GEL has adhered to a strict monitoring, management and mitigation procedure during drilling and operation to ensure that any resulting minor induced seismicity is understood by members of the local community.[18]

In August 2020, the project's operations have been further funded by the UK Government through the Getting Building Fund, with GEL receiving a share of £14.3 million to also demonstrate that lithium can be produced from geothermal brines with a zero carbon footprint.[19] To date, the project has cost in the region of £30m. In January 2021, GEL agreed to sell 3 MW of power per year for 10 years to Ecotricity.[4][5]

Geology

The Cornubian granite batholith stretches from Dartmoor to the Isles of Scilly and contains a high concentration of heat-producing isotopes such as thorium (Th), uranium (U) and potassium (K). This natural heat production means that the heat flow at United Downs is approximately double the UK average at 120 mWm−2, and geothermal gradient is ~33-35 °C/km, almost 10 °C/km hotter than large parts of the UK.[2][20]

Cornwall is also divided by a number of faults and fracture zones with a preferred orientation of NNW-SSE or ENE-WSW, believed to have been reactivated by post-orogenic extension after the Variscan Orogeny, with the ENE-striking fractures hosting magmatic mineral lodes and ‘elvans’ that were mined throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.[21] NNW-SSE striking 'crosscourse' faults, which are often long and show evidence of significant displacement, are aligned parallel to the regional maximum horizontal stress and therefore are believed to be the most ‘open’ structures, providing enhanced permeability.[22][23][2]

The United Downs wells encountered three main lithologies: 1) Killas (a low-grade, regionally metamorphosed and deformed mudstone of the Upper Devonian Mylor Slate Formation[24]); 2) Microgranite; and 3) Granite.[1][2] The wells also intersected open NW-SE-striking fracture corridors related to the major 'crosscourse' of the Porthtowan Fault Zone.[1][2]

Community Engagement

GEL’s community engagement programme has been extremely important for the successful continuation of the United Downs geothermal project. From an early stage it was established that time, effort and a personal approach were crucial to finding the extent of the community and reaching a diverse range of its members. As a result, accurate, up-to-date information has been communicated to a broad range of the community via public visits to the GEL site, external presentations to interested groups, exhibitions at public events, printed flyers, online resources and through the wider media.[25]

An inclusive and interactive education programme and careers events have also been run by GEL to give an insight into Cornwall’s new and growing geothermal power and heat industry to students throughout Cornwall.[25][26]

GEL also established a significant community fund, supporting sustainable and community-led projects in four local parishes with a shared grant of £40,000. This ensured that the local economy , people and environment benefitted as widely as possible from the project.[27][28]

See also

Geothermal power in the United Kingdom

References

- Farndale, H. and Law, R. (2022). "An Update on the United Downs Geothermal Power Project, Cornwall, UK" (PDF). PROCEEDINGS, 47th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 7–9, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Farndale, H., Law, R. and Beynon, S. (2022). "An Update on the United Downs Geothermal Power Project, Cornwall, UK". European Geothermal Congress, Berlin, Germany | 17–21 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "'Hot rocks' power plant plans revealed". Western Morning News. 13 October 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Sold! The UK's first geothermal electricity to the grid |". 4 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Ecotricity seals 10-year agreement to take geothermal power from Cornish plant". Energy Live News. 7 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- "Geothermal power plant set to become a reality in Cornwall". New Civil Engineer. Emap Ltd. 19 October 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- Halper, Mark (11 October 2009). "We're mining for heat in Cornwall". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- Rezaie, Behnaz; Rosen, Marc A. (1 May 2012). "District heating and cooling: Review of technology and potential enhancements". Applied Energy. 93: 2–10. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.04.020. ISSN 0306-2619.

- Ozgener, Leyla; Hepbasli, Arif; Dincer, Ibrahim (1 October 2007). "A key review on performance improvement aspects of geothermal district heating systems and applications". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 11 (8): 1675–1697. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2006.03.006. ISSN 1364-0321.

- "Geothermal power plant gets funds". BBC News. 21 December 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- "'Hot rocks' geothermal energy plant promises a UK first for Cornwall". Western Morning News. 17 August 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Drilling to begin for Cornwall geothermal power plant in 2011". The Guardian. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "Geothermal projects get funding boost". The Ecologist. 22 December 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- "UK's first geothermal plant given go-ahead". Financial Times. 15 October 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "£6 Million Grant For Geothermal Energy Project in Cornwall". Invest in Cornwall. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Geothermal project on rocks after funding blow". this is Cornwall. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Jupe, A., Law, R. and Farndale, H. (2022). "Implementation of an Induced Seismicity Protocol for the United Downs Deep Geothermal Power Project, United Kingdom". European Geothermal Congress, Berlin, Germany | 17–21 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Seismicity – Geothermal Engineering Ltd". Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "LEP agrees £14M investment". Business Cornwall. 4 August 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Beamish, David; Busby, Jon (24 March 2016). "The Cornubian geothermal province: heat production and flow in SW England: estimates from boreholes and airborne gamma-ray measurements". Geothermal Energy. 4 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s40517-016-0046-8. ISSN 2195-9706. S2CID 55659348.

- Alexander, A.C. and Shail, R.K. (1995). "Late Variscan structures on the coast between Perranporth and St Ives, Cornwall" (PDF). Annual Conference of the Ussher Society, January 1995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brereton, Robin; Müller, Birgit (15 October 1991). "European stress: contributions from borehole breakouts". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 337 (1645): 165–179. Bibcode:1991RSPTA.337..165B. doi:10.1098/rsta.1991.0114. S2CID 123973444.

- Puritch, E.; Routledge, R.; Barry, J.; Wu, Y.; Burga, D. and Hayden, A. (2016). "Technical Report and Resource Estimate on the South Crofty Tin Project, Cornwall, United Kingdom". P&E Mining Consultants Inc. For Strongbow Exploration Inc. Technical Report 295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Record details | Geology of the country around Falmouth : memoir for the 1:50 000 geological sheet 352 (England & Wales) | BGS publications | OpenGeoscience | Our data | British Geological Survey (BGS)". webapps.bgs.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- Charman, J., Law, R. and Beynon, S. (2022). "Effective Community Engagement: The United Downs Geothermal Power Project, Cornwall, UK". European Geothermal Congress, Berlin, Germany | 17–21 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Education – Geothermal Engineering Ltd". Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "First community grants awarded by United Downs Community Benefit Fund". Cornwall Community Foundation. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "CCF announces funding from the United Downs Geothermal Community Fund". Cornwall Community Foundation. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

External links

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии